THE BARROS PAWNS: A free serial for Lockdown – 25-27.

A novel of war in Mozambique by Peter J. Earle

Author of 6 southern African thrillers.

TWENTY FIVE

TWENTY FIVE

The crater became a brass bowl and sweat dribbled down the faces of the two men crouched behind the rocks, soaked their shirts and stuck them to their backs, until it seemed that they had no more moisture to give. Their mouths were slimy and their lips cracked. Even so, they were thankful that it was well past mid-summer. It was after ten o’clock, now, quiet but for the small birds and the sharp yelp of lappet-faced vultures at their feast. They couldn’t see the body, but they guessed that it must be da Silva who had fallen without a parachute. The mass of ugly birds were only thirty metres from them; huge, dark, untidy; tearing and delving. Around them, darting in when they could, were a few smaller hooded vultures, mindful of the huge beaks of their brethren.

His lean face lined from squinting into the glare, Geoff Nourse scanned the slope around where the mortar lay. It was no comfort to know that he was six shots into his last magazine. He said, abruptly, “How’re you off for ammo, Dan?”

McNeil quartered the slope over the vultures; besides the birds, nothing moved. But he knew what lay behind the flat rocks beyond, effectively cutting off any attempt they might make of climbing the cliffs, at their backs, in daylight. Frelimo had not fired a shot in many minutes, but they didn’t need to; all they had to do was wait for the South Africans to try their luck. McNeil grimaced. This was it, then. They were to die here in the wilds of Mozambique; by a quick bullet, if they were lucky, by dismemberment, if they were taken alive. Then, there was the thirst that was already a factor, squeezing them, losing moisture that they could not replace. Still, they were unlikely to be alive long enough for thirst to make a big difference…

“Ten or twelve, no more. I wonder why that other mortar stopped? Must be out of shells, except for those with that bitch down there.” He nodded at the nearer tube. “They should have grenade launchers and rockets, but they have thrown nothing else at us. I s’pose everything is out in the field to use on the Portuguese.”

“Does seem strange,” Geoff sucked at his dry mouth to loosen his tongue, “but your theory must be right. Now, you clever bugger, how do we get out of this one?”

Dan grinned, suddenly; his feeling of hopelessness lifting. Geoff hadn’t given up and he was trusting Dan’s experience to get them out of this pickle. He wished that he’d had Nourse with him in the Congo. Okay, analyse. They had twenty shots between them, or two short bursts each. They couldn’t go up; they’d be cut to pieces. The same result if they went down. Except for small boulders, they were exposed all round. All they might survive would be a short dash with the other giving covering fire with the last of their ammo…

“It’s quite simple, my china,” he said, the idea suddenly leaping into his mind. A chance, a slim tenuous, odds-against chance. “Give it an hour. Let them sweat and get cramp and get thirsty. Let them think that we are never going to try it. Then, we try it.”

“Up the kranz? You’re mad, bloody bonkers. Captain, this is your crew speaking; we hereby mutiny.”

“Shut up, crew, and listen. It may be a poor chance, but at least it’s a chance. No, not up the cliffs. We go downhill. You…”

“Now I know you really have a screw loose. What preference do you have for being shot at close quarters instead of being shot at…?”

“Oh, Jesus, Geoff, shut up a minute. You take my ammo and put your rifle on rapid. You cover me. As we know, they’re in two main pockets and by now, could be more, pretty spread out. You have to cover the lot in very short bursts. I’m going to try for the AKs on the bodies down there near the mortar. I think the mortar is out of sight of the johnnies out here on my side so I’ll have only those under cover near the mortar to contend with.”

“Only,” muttered Nourse, “That’s all. Nothing to it. And if you don’t make it, what the hell do I do them?”

“Then you can be Captain.”

McNeil fired as a head and weapon snapped into view beyond the vultures. The birds rose, flapping ungainly. The shot echoed back from the cliffs for nearly a minute before silence fell again. Nothing else happened.

“Think we’ll have any ammo left by then?” Geoff asked, sardonically, as the birds settled again. “What; when our hero has taken the position? I suppose, then, I also have to run like hell?”

“Faster than that, but I’ll have a cold beer waiting for you.”

Geoff wished he hadn’t said that, he could see the golden glass with the condensation trickling down and his furry tongue rasped over his dry lips.

The sun climbed and turned on the heat. Now and then they saw it wink on binoculars across the crater and they wondered who it was over there, waiting for this little pocket of resistance to be wiped out. They had guessed, by now, that the whole charade had been arranged as a spectacle for someone. The South African uniforms, the weapons. Nourse thought of the stupid little transmitter pen in his pocket and asked Dan where in the hell Brand and Cecile were, smothered in their cloaks and tripping over their daggers. Fat lot of help they’d been.

“And I had the man they were after in my hands and I told him to walk away up the mountain. Even wished the fucker luck! Still, he’s changed sides, hasn’t he?”

They both hoped that it hadn’t been the worst mistake of their lives, but it was too late to do anything about it now. They would be vulture food in a little while. They reckoned that they had as much chance of making it out as they had of finding that cold beer Dan’d promised Geoff.

You’re as good as dead, their little voices said, so just take as many of them with you as you can.

The silence and the heat and the minutes dragged on. Across the crater, three or four men could be seen making their way from the bottom of the cliffs up to the bottom of the dent and through it. As McNeil pointed, they knew they were looking at the normal route in and out of the circular valley. Only properly equipped climbers could scale the cliffs, anywhere else, except for the route the escapees had taken that morning. It was McNeil’s guess that the Frelimo just leaving were either being sent to circle around the rim to fire down on them from above, or to bring more mortar shells or an RPG2 rocket. Either way, Geoff thought with a bilious feeling in his stomach, they won’t finish whatever it is before he and Dan made their move. His watch said half an hour left. For what? To live? He glanced at Dan, but he gave nothing away; he merely grinned. Surely he, too, was quaking inside? Nourse returned the grin.

Suddenly Nourse fired and a man fell on top of the mortar. Another grabbed desperately at the weapon under the body of his companion, but hardly moved it before Nourse’s second round took him in the hip. A third man picked up two shells and started back. McNeil took his attention off his own sector to watch in agony as Nourse’s next shot completely missed the shell carrier. Again Nourse’s weapon crashed, but his own side was alive with attacking men and he was feverishly firing, seriously distracted by rising vultures. Something slapped his shoulder, and then it was over.

The shell carrier was down, twitching, ten metres from the cover he had sought – now it only needed a man to risk a short dash to retrieve it for the other mortar. More men had made the protection of the rocks beyond the remains of da Silva’s body which now had the company of two Frelimo who had not made the dash. Another had found a depression just beyond the others, but Dan said he could just see the edge of his shoulder as he flattened himself for dear life into the rock.

Geoff watched with concern as McNeil fingered the lava fragment that was embedded just under his collar bone. He said that the whole area still felt numb after the initial shock of impact. Slowly, the feeling returned in waves of pain and blood began to trickle down his chest and soak his shirt – just another blotch on the camouflage. The time to move was now – before this shoulder stiffened and the enemy had time to lick their own wounds and before they had to use any of their fast diminishing supply of cartridges.

More specks appeared in the clear sky. More food in the larder, so more guests for dinner, Geoff thought as his pulse gradually returned to normal. He risked a glance at Dan to see the ever widening crimson blotch on his shoulder. There was a muffled click as McNeil’s magazine came free. He handed it to Nourse and Geoff realised that Dan had decided to go. Now. His gut knotted. The last drop of saliva dried up. He saw McNeil clip another magazine from the pouch on his leg and realized that it was the blanks with which they were issued. McNeil caught the glance and smiled tightly.

“Some muzzle blast to fry their eyebrows. I do have one live one up the spout. Do you now have half a mag?”

“More than half, eleven, I make it.” Geoff deftly thumbed those cartridges from Dan’s magazine into his own and replaced it. “So, you’re off then? Send a post card.”

“You’re alright, Geoff Nourse. Just one thing. The one who’ll move first will be the one that’s the most uncomfortable. And there he is. That one over there who thinks he’s a chameleon. Drop him first, then lift your burst to keep the bugger behind him down, then slam that nest of sods around the mortar. And watch you don’t tickle my arse. Okay? That’s it, up yours, I’m off!”

There were a few metres of good cover in the tangle of boulders, then they became more scattered and the surface was steep rock and gravel. McNeil was in full stride by the time he burst into view, making a minimum of noise as he ran on his toes, hurtling down the slope, incapable of stopping even if he’d wanted to.

He’d been right about the chameleon. Geoff’s first two bullets hit him in the chest even as he came to his knees. One man further back also half rose but dropped as the burst lashed gravel into his face. Then the muzzle swung, the splatter of rock chips hit the chest of the man near the mortar who had risen to meet McNeil’s wild dash. The onslaught threw him backwards and his weapon spewed into the sky. Another man who had been crawling after the mortar rolled onto his back and lifted his AK, but McNeil’s single live round went through his throat, then the R3 jammed on the blanks with not enough gas to eject. Even as Dan dropped the useless weapon, he was at the mortar and its complement of dead bodies. With a shower of flying gravel, he allowed his knees to buckle and he collapsed onto the nearest corpse, his hand reaching desperately for the AK at its side, his mind screaming: I’ve made it! I’ve made it! – while hardly daring to believe it.

He pulled the corpse around so that it afforded some scrap of protection and uncovered the spare ammunition pouches. He put short bursts into the rocks round about. The weapon clicked empty and he tugged feverishly at the pouches for another, knowing that he was right out in the open. His shoulder was now a sea of pain and his head spun. It sagged onto the chest of the Frelimo as he blacked out.

His heels were dragging on the rocky ground when he came around. He started to struggle, so Nourse put him down.

“So, walk, then, you lazy bastard,” Nourse grunted. They were almost at some rocks that McNeil eventually recognised as those behind which those men attempting to recover the mortar had lain. From the distance came the rattle of another AK; it licked the dust some twenty metres off and crept towards them as the user corrected, then ran out of ammunition. Then Nourse was back with the mortar.

“Set this up, will you, Dan, while I go and get something to fire through it. Hey, Dan?”

“For Christ’s sake, what’s happening?” McNeil groaned, rolled to his knees and turned to watch Nourse trot with no effort at concealment across to the half dozen mortar bombs lying where the weapon itself had once lain. Besides themselves, the only things that moved were the vultures. Except across the valley…

“Hey! They’re pulling out!” McNeil caught sight of some little figures snaking up the route to the notch.

“Seems like it, Dan,” Nourse laid his load down near the base plate. “Now, give me a hand to try and stop them, will you?”

With McNeil aiming and Nourse loading, they sent three bombs off to the base of the notch. Slowly, the dust cleared. They could see nothing moving. The crater was quiet again and the noon sun beat down, uncaring, impartial.

“Help me with this shoulder, will you, and for Christ’s sake, tell me what…”

“What happened?” Nourse found the strength to grin, wryly. Reaction was now starting to set in and he felt weak at the knees. “Very little, actually. When you set out on your dash, the opposition had all but had it, already. There are probably a couple of Frelimo out in the rocks who wish that Mozambique was also on the National Health, but they seem to be lying doggo until we get the hell out of here, I guess. The rest seemed to be trying to run for it before we – hold on, I can see it! It looks like a piece of rock.” He shifted the lips of the wound so that he could see into it. The edge of the collarbone showed briefly white in it before the blood flowed again. Nourse managed to work the sliver of stone loose and out of the wound while McNeil called him all the filthy names he could think of.

“Yo mama din brung yo up proper, mon!” Nourse said, keeping a weather eye on their surroundings for any sign of active enemy survivors and the tension still made his skin crawl. All he could think of was to get out of the crater and back into the relative safety of the surrounding bush. He armed them with AKs and five full magazines apiece. He nudged the mortar with his boot.

“How do we blow this thing up?” He asked Dan who told him to place the bombs, noses together, to the base plate and the barrel on top.

“Hit the base plate with a burst when we are safe in cover. Now, let’s get the hell out of here, for Christ’s sake!” Dan was feeling better with the piece of stone removed, but the whole shoulder was stiffening and ached abominably. It was now bandaged with strips from Nourse’s trouser legs as he had turned them into shorts. He swayed drunkenly to his feet and took the AK that Geoff handed him with a look of concern. He waited for his head to clear, grateful that it was his left shoulder, not his right. He set off after Nourse, across the floor of the crater. From a safe distance, the latter detonated the mortars with a carefully aimed burst against the base plate.

The ground still sloped down for awhile, but cover from the enemy, such as there might be, increased with gnarled fig trees, acacias, shrubs and bigger boulders. In one such cluster of rocks, there was a small marshy patch that denoted a spring. Here a path started and led to another, larger spring where they drank, deeply, gratefully, then to another. Although the vegetation increased, too, by climbing on higher rocks, Nourse was could see over it and was able to be relatively sure that there was nobody lying in wait. As they approached the cliffs after half an hour’s careful advance, McNeil became aware of the caves. He called to Geoff in the lead.

“Hey, come back here a minute, will you?” He sat and lit a smoke, Nourse squatting beside him, cradling his AK, his eyes peeled. “Do you remember what da Silva said? You told me that he told you, when you were painting the Dak, that they were going to drop us into the Frelimo main camp?”

“Ja, so what?” Nourse looked at the pitted, towering cliffs and frowned. “So, the birds have flown, if they survived the mortars.”

“How many did you see, running up that path or whatever it is, before we blotted them out? Five, six? Could you make them out? Weren’t they all black guys, in camo?” Dan’s voice rose in excitement as he became sure of his logic.

“Weren’t we expecting some special spectators, so that our little exhibition had someone to impress? What happened to them, Geoff? I think the buggers are still here, in those caves, waiting to shoot the shit out of us if we go nosing around in there.”

“Oh, shit,” muttered Geoff, feeling quite sick, suddenly. It made sense. He slid down behind a boulder, sweat starting out afresh on his brow. “Then, I’m not curious about what’s in there. I mean, of course there are a hundred cases of cold lager in there, but who wants one, anyhow? Surely we can go around that far side and meet their path half way up. We could be out of sight of the caves, most of the time. Hopefully. Thank God they seem to have no more mortars, or rockets!”

Still pondering the enemy’s lack of a larger armoury, but assuming the rockets and mortars such as they had encountered in the fights of Serra Chimbala and at the Pompue, were in the field, or supplies had run out, they made for the opposite cliffs. While keeping away from the threatening caves, they still hoped that their route would seem natural to any possible observer. An hour later, they reached the path and warily began to trudge up towards the dent. They were half expecting to meet the group that had escaped up it recently. They found some body parts at one of the mortar craters and knew that they had taken out at least one man.

The worst ordeal was climbing out of the dent to attain the main ridge, which, although up and down, actually had some sort of path worn on it, obviously a patrol route. They slowly circled the crater to finally arrive at the further dent where the others had made good their escape that morning. It was sundown when they reached the spot where Theunissen, Muller, Visagie, Schulman and Sanderson has waited for less than half an hour. Nourse ferreted around morosely in the fading light.

“The bastards didn’t wait long, then.”

McNeil nodded. He knew that Nourse was adept at reading sign and didn’t doubt what he said.

“I just do not understand why Theo moved out without some sort of farewell gesture. Not even a message. Perhaps he gave us no chance of survival and decided that waiting was a waste of time.” Dan said, not without a little bitterness.

Geoff smiled wryly; he had given themselves no chance, either! Perhaps some Frelimo had forced them to move? Still, Theo had been acting pretty strange, of late. Maybe he was getting too old for this caper.

They set off on the trail of the others in the remaining light and stopped when they started to trip over things. They had nothing to eat and nothing to drink. McNeil’s shoulder was a block of throbbing pain. Nourse gathered some grass and dried mopane leaves into a hollow in the ground in the shelter of some huge rocks. They felt a little cold, now, but dared not risk a fire this close to the mountain.

“I’m going to have a smoke, Dan. I don’t care if there are fifty Ters out there waiting for me to light up. God, I’m buggered. I could sleep for a week.” Nourse lit two cigarettes and passed one to McNeil. There were five left in his packet. After five minutes, they stubbed them out and crawled into their nest, not bothering to keep watch.

TWENTY SIX

The silence was broken with a curse from General Mucongáve. Smuts said something to him in the Sena tongue in a sharp tone and it sounded like the general told him to shut his white trash mouth. John Alistair huddled a little further back into the cave. He shivered in fear. He wondered who would shoot him first; Smuts or the general or the two South Africans who were outside.

Somehow or other, things had gone wrong. It was not difficult to realise that the whole thing had been set up for his benefit. When the Dakota first began to disgorge the paratroopers, Colonel Wanga, to whom he had just been speaking in French, had muttered in that language; “The fools! They’re much too far away.” Then, of the first two, one had plummeted straight into the ground. The rest has poured out in a bunch then, after a pause, two had come out in a most unmilitary fashion. No sooner had they hit the ground than they, instead of attacking, had shed their kit and most of their rifles and headed in the opposite direction! Alistair’s look of bafflement had been seen by Smuts who had tried to explain.

“Must be a recce party. Ha-ha, I bet they didn’t expect to jump right into the enemy’s lap! Look, they got such a fright; some of them have thrown their rifles away! They know they haven’t got a chance against us.”

“Yes,” Alistair had said, feeling sick in the pit of his stomach. “Is this the first attack by air? I see the plane had no markings. Where do you suppose it operated from?”

Smuts eyes had narrowed, briefly, but all he had said was, “Probably from over the Rhodesian border.”

The crater had echoed with gunfire and General Mucongáve cursed again as it had been apparent that there was still some considerable distance between his men and the fleeing South Africans, if indeed, that’s who they were. Captain Chitamba returned briefly for a mortar and bombs, about which he and Colonel Wanga had an argument. Eventually, Chitamba had left with eight bombs or so and a murderous backwards glance.

“We are very short of ammunition, here at the moment,” the thin Colonel had explained to Alistair. “There is some on its way from the Zambian border and we expected it here last week, but -” he shrugged, as if to say that very little of what was expected actually happened. Alistair had noted that, so far, none of the whites that appeared to be armed had fired a shot. He had seen a Frelimo, shooting at the fleeing men, go down, then a second one. The lighter crack of a pistol had come to their ears. General Mucongáve had demanded to know what was happening. The roar of a grenade came just after that, the only one to be heard, that day.

Alistair, straining his eyes, had seen the faraway ants that were men, strung out, moving slower as they began to climb, and the pursuers closing the gap. Chitamba was directing his mortar crew to set it up at a spot where the ground was not yet too steep, and, Alistair had thought, this would be the end of them. Another victory against the imperialist racists. He would be taken to see the bodies, what was left of them, in their South African uniforms, so that his indignant words would bear witness and stir the world’s indignation at the military intervention etc. etc.

Then he had seen that some sort of resistance had been set up by someone in a cluster of boulders at the foot of the face that the fleeing men were trying to climb. Chitamba’s mortar had fired twice without effect and that set the general to cursing again. He had roared a command to Colonel Wanga who had taken three men and scurried off to the caves to fetch another mortar and four bombs. Even then they had seen that Chitamba’s mortar had been abandoned as the riflemen in the rocks had harried the crew. Someone else – it must have been Lieutenant Mtiwa – had led a party of men in a flanking movement, but it had slowly petered out as their cover thinned and their numbers had diminished.

The ants had been nearly at the top of their climb when Wanga fired. Nasty, shuddered Alistair. Wanga was an excellent mortar man. The bombs crashed onto the face, spewing rock and splinters into the air. General Mucongáve had roared his approval as the top-most ant had been shredded and cast away. Crash, crash again, then silence. General Mucongáve had looked at Wanga.

“Finished, my General,” he had reported, sadly. The general’s lips had thinned in frustration.

“Get some from Chitamba!” he had ordered. A man hurried away. Twenty minutes later, there had been a rush on the mortar and its bombs, lying in the open. They almost made it, but, with a furious battle, it had fizzled out. Alistair had found himself hoping that the South Africans would make a getaway, even though, if they did, that would jeopardise his own position seriously. Damn the Commies and Frelimo for their sneaky little tricks. Sweat had broken out on him in a fresh wave of gut-shrivelling fear. He had tried to keep his face unconcerned, but he knew that Smuts was watching him and he prayed that he had not given himself away.

*****

Whilst General Mucongáve had issued orders that Wanga take some men and circle the mountain top to try and winkle out the marksmen in the rocks, Smuts had watched helplessly as a figure had gained the safety of the rim of the dent and disappeared. He, too, had been sweating with fear; the whole affair was going sour and there was nothing he could do about it. He had read Alistair’s face like a book and knew that he would have to arrange his death, but that was a mere detail. The publicity side of the plan was less important than Sanderson getting away. He had tried to retain some hope that Sanderson had felt that he had been in no position to fake a surrender; that he hadn’t gone back on the deal; that he would return when he could. Smuts had been sent an expert interrogator to make Sanderson shed his secrets under pressure if the need arose, but it had not been necessary. There was the down-payment, of course, but the expert could not guarantee that they could sift the complete complex firing procedure from Sanderson’s mind with the degree of accuracy required. There had certainly been no intention of paying the balance or allowing Sanderson to live after they had gleaned whatever military secrets to which he in his position had been entrusted.

Through his binocular, Smuts had picked out the stocky figure, crawling up the face. It was easy to pick out the blue arm band. He had begun to feel sick – the chestnuts were well and truly in the fire and he could think of no way to snatch them out. The price for failure would be his own life. There had to be a way of getting Sanderson back; there had to be.

The battle had quietened down to odd shots; each was a quelled attempt to rush the rocks. Suddenly, a white soldier dashed from cover for the mortar, whilst a fusillade of shots banged out, then it was silent. Smuts waited only long enough to be sure that the mortar had fallen into enemy hands then he grasped the general’s shoulder.

“Comrade General, we must get into shelter of the caves before they can use the mortar!” General Mucongáve had stiffened at Smuts’ touch, but he had seen the sense of it. He had looked at his remaining men, shrewdly, his eyes slitted. He snapped an order at a sergeant to take five men up the trail and hold the top in case the South Africans went up. They set off at the double. They were in fact a decoy while the general, Smuts, Alistair and two other men crawled into the caves. The general and Smuts had a hurried conference that they made certain that Alistair couldn’t make out; then Smuts slipped out, again crawling. The general and two men set up a machinegun back from the mouth of the cave.

Smuts was in one of the further caves with the Chinese soldiers when the mortar started. They gripped their AKs and huddled in the dark, waiting.

“No, Captain!” Smuts had whispered in Chinese, “You must not show yourselves. I think we can get them as they come this way, as they surely will, but they must not see you in case either one gets away. No, of course they won’t, but there is also the English journalist. We will take him back to Malawi and arrange an accident there, otherwise someone may come looking for him. We cannot risk that.”

He pretended not to see the Chinese captain smile in the semi-dark. It was a smile of contempt. The man knew that Smuts was not obliged to discuss these matters with him, a mere Captain of Communications in the Chinese Peoples Army. It was fear he could smell on Smuts, and he knew that things had gone radically wrong. It would be Smuts who suffered the consequences. It was the captain’s job to command the four radio operators with him and make sure that their equipment was functional. Well, for now. Smuts thought that the captain probably had other capabilities if he was called upon to use them. He saw the bastard smile again, and he suppressed a shudder. Smuts knew the captain didn’t like him and would find it a pleasure to liquidate him if he got the order to do so.

They were safe in the dark of the cave, but Smuts positioned himself so that he could now make out the two South Africans at the foot of the crater. They had stopped. There was a burp of AK fire and a booming explosion and he had realised that they had destroyed the mortar. The two men made towards the caves. All the watchers tensed as they stopped once more.

In his cave, General Mucongáve would be cursing. The bastards were skirting them, and although they were in range for a long shot, they were rarely in sight. An hour passed before Smuts deemed it safe to come out.

“Is there nothing we can do?” gritted Mucongáve, “I must warn all my men to look for them. They must be heading for the Zambezi.”

Smuts nodded, unhappily. “What is more important, General, is the man, Sanderson. It would be a pity if your men shot him, but he must be stopped. He must be brought back here, alive.

The general grinned without humour. “It seems your plans have come unstuck, Comrade.” There was a sardonic inflection on the last word. “When Wanga returns, he will personally see to it. All the whites that have survived will head for the big river; they will go downstream towards Mutarara, where there is a garrison of Portuguese soldiers. There are some trading posts on the way, but they mostly co-operate with us. They are too afraid not to. We have informers in all the aldeamentos along the way. Few will help them. We will get them all. Will you be going with Colonel Wanga?” The yellow eyes watched his. Smuts knew that he would have to go. Getting Sanderson back was his responsibility. He nodded. It was Frelimo country. There was a good chance that the whites would not get away. His own life depended on it…

“Keep the journalist here, Comrade General. Please guard him well. I must take him back to Malawi and arrange an accident there. He is of no further use to us.”

The general shrugged. It was no concern of his. Smuts guessed that he would be thinking that these foreigners were too clever for their own good. It had been a bad day, he had lost many men; Chitamba and Mtiwa among them, it seemed. The general sent a man down across the crater to look for wounded men and recover such arms and ammunition as he could. It would come, he knew; a free Mozambique, but he wished that it could be without the help of the Chinese or the Russians. They would extract their pound of flesh, he knew, and the price would be dear. Smuts saw him go to his radio with his operator and heard him as he called up four of his bands and gave them their instructions. They would all head for the Mutarara – Bandar road by the shortest route and put out the word as they went. General Mucongáve obviously thought it a nuisance, but it was certain that they would get them all in a day or two. Most were unarmed. These two that had caused the most damage were the biggest problem, but he warned his men to be careful. He had told them that they were Sul Africanos and that they were to leave them where they fell and not to touch their uniforms.

Smuts went to see Alistair. He found him in the shade near the cave mouth, smoking, fairly composed. They kept up the charade for the time being.

“Well, there you are, Mr. Alistair. They’ve never sent paratroopers, before, so it looks as if the South Africans are hotting things up for us. For the true Mozambicans, I mean.”

“Yes,” Alistair said. “You will have to move camp now that they know where your headquarters are.”

Smuts sighed, “I suppose so.”

Not if we stop the South Africans in the bush, he thought savagely, kicking his foot abruptly against a rock with sudden temper. He noticed Alistair shiver. He realised that the man knew that his chances of survival were not much more than nil.

TWENTY SEVEN

The midmorning sun threw a vicious glare off the planes, the roofs, and the shining tarmac itself, so that the majority of onlookers in the concourse of Manga Airport, Beira, including Morné Brand, wore sunglasses. A DETA Airways Boeing 707 from Lourenço Marques touched down with minimal bounce and little white puffs of smoke exploded from the wheels. In less than seven minutes of its coming to a standstill in front of the terminal, the first passenger was squinting into the glare from the top of the stairs.

The midmorning sun threw a vicious glare off the planes, the roofs, and the shining tarmac itself, so that the majority of onlookers in the concourse of Manga Airport, Beira, including Morné Brand, wore sunglasses. A DETA Airways Boeing 707 from Lourenço Marques touched down with minimal bounce and little white puffs of smoke exploded from the wheels. In less than seven minutes of its coming to a standstill in front of the terminal, the first passenger was squinting into the glare from the top of the stairs.

Both Bates and Duvenage had been on the flight and although they knew each other well, neither spoke to nor acknowledged the existence of the other. Once through the official formalities that plagued even the internal flights in Mozambique, Bates made for the lounge and, catching sight of Brand, joined him. They swiftly went to the car park where they got into a grey Landrover and followed the taxi that Duvenage took into town to the railway station. In his wing mirror, De Souza, driving, could still see the scooter that had been dogging them since he had picked up Brand and Cecile Cradock earlier that morning. Beira was just not crowded enough to lose it. Eventually, Brand told him to stop trying. It had got too late for mere observation to hinder them. It was too bad that De Souza’s cover was blown, but they were committed to action, now, in a desperate bid to find van Rooyen. The scooter stopped at the kerb as they pulled into the station car park. The mulatto on the scooter tucked his chin into his jacket to make use of the radio he had there.

They watched as Duvenage pulled his soft leather suitcase up under his arm and stepped a few paces back to admire the façade of the old building to give the taxi time to disappear across the bridge over the Rio Chiveve where it entered the docks. There were some twenty vehicles in the forecourt where he stood. There were several Landrovers – it was 4×4 country – but he put his money on a new grey station wagon with curtains in the windows abaft the front seats that had just come in. He was an athletic man with an easy, springy stride, an even six foot tall with a wiry frame, dark, straight hair, brown eyes, lean face and a quirky mouth. He disappeared into the brightly muralled concourse.

“All a bit pointless,” said Brand, “but I suppose they aught not to know exactly when we leave Beira and in what direction and how many there are of us. Take this guy out before he can use his radio again.”

Bates slipped out of the back seat. He was two inches under six foot, with a barrel-chested and powerful frame. He was blue eyed, had blond very curly hair, and broad face with a wide mouth. He set off smartly towards the road to the front of the scooter. Cecile set off into the station to find Duvenage. The driver, De Souza, was a Latin, short, wiry; wavy black hair. He opened his door and took the long route along the road to the entrance and walked out behind the scooter. The mulatto turned and watched him approach, puzzled, but beginning to look nervous.

“Desculpe, o Senhor, mas tenho horas?” He asked for the time. Bates hit him hard from behind and caught him as he fell. They eased him to the sidewalk, took his radio and propped him against the rear bumper of a parked vehicle. Bates bent the mudguard into the wheel and put the scooter on its stand. They sauntered back across the car park to the grey Landrover. Cecile reappeared with Duvenage and the vehicle paused to pick them up as they left. There was no reaction from the few people around. The vehicle circled the traffic island, pausing under the windmill of the little Moulin Rouge for a minute, and then drifted casually past it. The street they were in was flanked by warehouses and workshops, where trucks were being unhurriedly loaded and vehicles unhurriedly repaired. Vehicles were parked half on the pavement and half in the street. The grey station wagon squeezed through and headed out of town.

Duvenage looked around. Beside him sat the good-looking blond girl whom, until now, he had never met. She turned a freckled face towards him and smiled in greeting as Brand introduced them. Up front sat Morné Brand, wearing a Stetson with a leopard skin band. He wore wrap-around dark glasses. Da Souza, whom he had met before, hooted at a trio of ragged street urchins who were rolling bicycle rims down the street. They scuttled away, grinning.

Brand explained the situation. He was almost sure that van Rooyen was not in Beira any more. The instructions to McNeil and Nourse had been to use the tracking transmitters to follow van Rooyen, but since they themselves had been taken prisoner, it stood to reason that they were not following him but making it only possible to indicate to Brand that they themselves were alive and to give their position. The fact that the mercenaries were incarcerated showed that things were coming to a head. With De Souza’s help, watching the movement of supplies and people, they had to deduce that the Barros hunting camp on the Mungari was the only possible place to have a look. It was reasonable to deduce that all players in the know would make sure that they were out of range when van Rooyen detonated his box of tricks, and the camp was such a place. There were no installations within fifty kilometres.

Then, early that morning, both transmitters had rapidly moved west.

“Both Barros’ DC3 and the Cessna logged flight paths for the Mungari camp, yesterday. Today, the speed and line indicated that they were aboard a plane.” Brand said. “Then the transmitters stopped abruptly in the middle of nowhere, where no known landing strips exist. That ruled out the Dak landing, but the Cessna could conceivably land on a road. However, when I kept in mind that most of the mercenaries were parachutists, it kept the Dak in the equation and suggested a jump. Still, where is van Rooyen?”

The grey station wagon swung left into the Avenida Massano de Amorim. It was peppered with pedestrians and unhurried cyclists and bumbling motorists that swerved to avoid potholes in the badly tarred surface without any warning, but Brand told De Souza to put his foot down.

Using the horn frequently and his voice more often, De Souza had them out of Beira without any signs of pursuit. As De Souza pointed out, the opposition would have no difficulty working out where they would head for and would radio a warning to the camp on the Mungari. They would know that it was a five hour drive and have plenty of time to prepare for them. Thus, there was only one thing that they could do to catch them by surprise and that was to arrive much earlier than expected.

In half an hour, they were through the little town of Dondo and passing the new Army barracks recently built on the site where, two years ago, two Rhodesian Special Air Services men had buried two canisters. They turned off the tar at the peeling signboard which said ‘Inhaminga – Vila Fontes’. In a further twenty minutes they arrived at a railway siding used for timber extraction where the rail ran parallel with the sand road. In the clearing of the forest next to the siding, was a large shed left over from the saw mill that the siding had served. Behind the shed stood a little five-seater red and yellow Bell turbine helicopter around which the present occupants of the shed stood gawping. The pilot sat behind the controls. As he saw them swing in, he fired up the turbine. De Souza stopped well clear of the machine and switched off. Duvenage and Cecile unpacked the rear of the Landrover, while Brand, De Souza and Bates went to meet the pilot. He slipped out of his seat; skinny, very handsome with long black hair. He seemed a trifle uneasy, but he flashed them a beautiful smile.

“You are the pilot, yes?” he asked Bates who was looking over the Bell in much too professional a way. “How many hours you got?”

“More than two thousand hours,” said Bates and passed him a folder with a licence and a logbook. The Portuguese pilot’s eyebrows shot up.

He took a key and opened the luggage bay under the rear seats for them then handed the keys to Bates. De Souza, in turn gave him an envelope, which the pilot checked, and the Landrover keys. He gave De Souza a Salisbury number where he could be contacted if they needed him earlier than the arranged three days. Duvenage packed the five steel jerry cans of jet paraffin into the compartment along with a carton of food and their personal effects. He and Cecile and De Souza climbed into the rear seats and took a long canister onto their laps. Bates locked up and got behind the controls with Brand beside him. The other pilot waved briefly as the Bell lifted and Cecile thought she saw a look of approval on his face at Bates’ handling. Then, with a harsh chukka-chukka of the rotors, it was turning and the road, rail and Landrover were lost to view. Within minutes, she could see the sea away to her right beyond the green carpet of woodland and they were heading north. Brand noticed that she shivered a little, probably in anticipation of what might lie ahead. It was a bit of the deep-end for the girl, but he was pleased with her, thus far.

Brand had gone over it with her, admitting that they might never find van Rooyen before it was too late. He had considered leaving her behind in Beira in case van Rooyen turned up there, but in the end decided that they keep their forces together, to her obvious relief. Brand had fretted at the delay in waiting for his two men to arrive. She had met neither of them before but Brand said enough to assure her that they were extremely competent agents. He had picked up enough from her seemingly professional questions that she was overly interested and concerned about the possible fate of one Dan McNeil. So she would be thinking of the man, afraid that something had happened to him, and trying to push these thoughts away so as not to impair her professionalism. Brand thought she had better be kept busy. He issued orders.

Duvenage opened a heavy fibreglass case and Cecile helped to assemble the three 7.62 calibre R3 paratrooper rifles with the fold-up stocks. Brand detected a flicker of nervousness from her, which was to be expected. It was just pre-combat nerves. He thought about De Souza. Perhaps the agent had softened with his foreign living, he reflected, but he had a good record and he knew he could be completely ruthless. His mother was Afrikaans; his father was a successful market gardener near Pretoria, an immigrant from Portugal in the thirties. All in all, he had the best team he could expect, but not the resources he would have liked.

As they began to cross open grasslands, they could see huge black smudges on the horizon that turned out to be vast herds of buffalo when they got nearer, grazing on the floodplain, unbothered by the noise of their passing. Brand opened the receiver and a map on his lap. With quick calculations he got the direction of the transmitters. He said nothing, but half an hour later, he triangulated with another direction and pinpointed them. His finger jabbed the map.

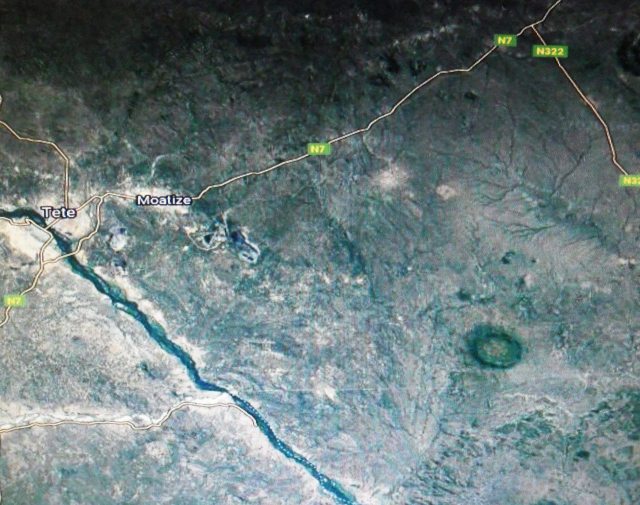

“They’re here, on this mountain, Serra da Muambe. What do you know about it, De Souza? It looks like a ring – like a volcano.”

De Souza shook his head. “Never heard of it.” He peered over Brand’s shoulder. “That area is very wild. There are some stores along the Zambezi that still trade with the locals, I understand, but some have been burned and others bribe Frelimo to leave them alone. It is very dangerous. The tracks are mined; the Army won’t go there.”

Brand nodded, frowning. He touched Bates on the shoulder and signalled him to lose height. Bates took the Bell down to tree-top level and turned to follow the river, moving inland. The banks of the river were heavily wooded, but away from it, there were large tracts of floodplain grassland, flecked with borassus palms. Soon, there were patches of dense forest on higher lying ground, increasing in frequency until it was mostly forest with occasional pans of depressed grassland with waterholes at their centres. Here, more buffalo, herds of sable antelope and waterbuck threw up their heads to watch them pass. Then, on a pan at the river’s edge, they saw the Barros hunting camp. There were eight separate bungalows in an L with three on the short leg and the rest on the long. The nearest, as they swooped in to land, was the longest; it had no verandas seemed to be a series of store rooms, workshops and garages. The rest were obviously the safari accommodation in the prime spots, overlooking the river, with the manager and staff quarters further back.

Bates put the craft down neatly just behind the garages to offer some protection should there be any gunfire. He kept the turbine going and stayed at the controls, while Duvenage and De Souza also stayed neat the machine at the corner of the building, their weapons ready but out of sight. They were ordered to keep their eyes on Brand and Cecile as they walked to the larger of the safari buildings. Both the Dakota and the Cessna were standing on the airstrip that stretched across the pan. An elderly black man was leaning on his broom on the veranda watching them.

“Where’s the Boss, Madala?” Brand tried asking in Zulu, hoping the man had worked on the mines at one stage of his life. To his surprise, he replied in English.

“He inside. Boss Senhor Barros, inside.” There was fear and apprehension in the old one’s face. Then Manuela Barros walked through the doorway, her hands in the pockets of her suede jacket. She smiled at them brightly but gave no sign that she recognised Cecile. She walked past the old man and turned in the centre of the veranda.

“I’m Manuela Barros. You would like to see my father? He is inside, busy with some books. Won’t you come in?”

Cecile’s nerves were tighter than a drawn bowstring, but she smiled back and left the talking to Brand; who introduced them as Professor Hanekom and secretary and said that he would indeed like to see Mr Barros. Together, they went up the steps towards her. They passed out of sight of the men at the corner of the garage.

“Don’t move, Brand!” There was an automatic in her hand and ice in her eyes. They froze, too far from her to jump her, knowing that she would not hesitate to shoot.

“Now, see here -” began Brand, relieved that coming here had brought matters out into the open.

“Shut up! Signal your men to come over, to shut down the turbine. Do it now!”

Brand moved to where he could see Duvenage and made a throat-cutting motion, then beckoned. Duvenage disappeared from view. They heard the turbine die then da Souza and Duvenage were walking towards them. Manuela could not see the Bell and would not have known how many there were of them, he hoped. As he turned back to face Manuela, it happened.

The madala hit Manuela over the head with his broom. She sensed it coming, but turned too late and it caught her squarely above the ear. In three strides, Brand took her pistol from her limp hand as she folded. The old man had his hand over his own mouth in surprise at what he had made himself do, his eyes wide.

“Get back!” yelled Brand to his two men out in the open. They turned and fled as a rifle started firing at them. Brand ran along the veranda. The man behind the palm tree and Brand saw each other at the same time but before the man could turn, he got a double tap in the chest and fell against the palm.

“How many men here, Madala?” Brand asked urgently. The old man was crouching against the wall next to him.

“Five with Senhor Barros, Sah, and two daughter, this one and Miss Rosa. They lock Senhor Barros and Miss Rosa in a room. Is too much bad!”

Manuela was sitting up, nursing a split ear that coursed blood through her fingers. Cecile was watching over her with a Beretta from a safe distance. Manuela began to curse the old man in Portuguese, then Cecile in English. Cecile said nothing, but eyed her warily, guessing how dangerous she was.

Duvenage and De Souza, now with their R3s, came at a weaving run, bending low while Bates covered both them and the chopper from the corner of the workshop. Brand took a deep shaky breath and stepped through the doorway. It was empty for a second then a man stepped into it, carrying a light bag in one hand and a pistol in the other. Brand had a brief impression that he was thin, tall and dark complexioned as he simultaneously saw the pistol in his hand whip upwards. Brand snapped off two shots at him before he could fire.

The man was thrown backwards, the travel bag skidding across the floor. He slid down the panelled wall and tried to lift the weapon again. Brand’s finger tightened on the trigger, but he knew the man’s strength and life were running out. The pistol sagged, the man sighed as it slipped from his lifeless fingers. Brand swallowed, his heart hammering painfully. This was the price of being back in the field again.

“Who’s there?” A quavering woman’s voice; English with a Portuguese accent.

“Miss Barros? Where are you?” Brand thought that the voice came from a room at the end of the passage. “We have come to set you free, we are friends.” Maybe. There was the sound of a lock being disengaged then the door half opened and a pale face with big brown eyes and black hair turned towards him.

“Who’s that?” Brand pointed at the man sitting in the passage. She looked and gulped.

“My father’s pilot. Is he…dead?”

Brand looked into the beautiful big eyes and nodded.

“Who is in there with you?” He could see two men behind her, a heavy, paunchy man with a beard streaked with grey, and an older man, slim, tired-looking, in a cream safari suit and a maroon paisley cravat. He recognised Barros from photographs that he had studied.

“Senhor Barros,” the paunchy man grabbed the other by the arm. “Tell this man that they forced me to help them! What could I do with those pigs, Ribeiro and Campos watching me all the time? Before God, I-”

Barros looked disdainfully down on the hand that gripped his arm until the other removed it, and then ignored him.

“My name is Barros.” He met Brand’s gaze squarely. “Who are you?”

“Hanekom, South African Bureau of State Security. Normally, I would apologize for my intrusion, but I think that in these circumstances, you won’t object to our coming uninvited. I am hoping that you’ll give me such information as I require, but firstly, I must be sure that nobody is going to shoot us whilst we’re talking. Will you come with me to identify a body and tell us who else is around that’ll give us trouble.” He stood aside for Barros. As he shut the door on Reis and Rosa, he told them to remain there for the time being. Duvenage came in a side door and reported that the place seemed to be deserted, not even servants.

“There’s only the old man who cooks for us and does some light housekeeping,” said Barros. “My daughter, Manuela, sent the rest of them away. My mechanic thought something was wrong and refused to go. Da Silva shot him…That’s my son-in-law… Everything seems to have gone… There were two men around, always armed, they should be about.” He obviously did not know what to explain.

On the veranda, he stopped in front of his daughter. Manuela was now sitting at a low drinks table, her hand over her ear, staring across the pan.

“Are you alright, Manuela? Have they hurt you?” He asked, gently, in their own tongue. She ignored him, only her mouth tightened a little, thinning the normally full lips. Her father watched her for a moment, puzzled, hurt, and then followed Brand to look at the body against the palm tree.

“Ribeiro.” Barros turned away. “It leaves only that rat, Campos, to account for.” He beckoned the old man, told him gently to bring beer and glasses. The madala nodded nervously and slipped away. Brand instructed Duvenage to take over the guarding of Manuela then he, Cecile and Barros went into the lounge. De Souza arrived to report that he had seen nobody. Brand warned him about the missing Campos and told him to keep his eyes peeled and to tell Bates to stay where he was.

“Where are the South Africans, where is this da Silva, where is that Sanderson man?” Brand asked Barros.

“Da Silva was Rosa’s husband, very charming, but I never liked him. But let me start at the beginning.” The old man brought a tray of beer bottles and glasses and an opener. Barros waved him away and poured for them himself. “I was born in Beira, I grew up here. I am surely the wealthiest man in Mozambique. I have plantations – tea, sugar, coconuts, cashews; a chain of general dealers, sawmills which export timber; I have interests in shipping and a lot more besides. All this is in Mozambique, very little outside.

“I am Mozambican first, Portuguese second. I would give my life for this country, if I thought it would keep it in safe, responsible hands for future generations of Mozambicans. Two years ago, I started to recruit men who would help to smash Frelimo. The Army was sinking into apathy, when, what the country needed was a concerted effort at this crucial time. Some of the men that I recruited were Army men and they were able to step up the pressure a little, but there were too many that would do nothing, given the choice. Defend only, not attack. Eventually, I tried to start my own army and bribed the regulars to leave them alone. Then Manuela persuaded me to recruit some South Africans, some of whom were ex-Congo mercenaries. This I did. But Manuela had her own plans for them. I had no idea that Manuela and Rosa’s husband were Communists…” His throat moved, constricting with emotion. He took a swallow of beer. Brand and Cecile sipped theirs, but said nothing. He had told them nothing new, as yet.

“In fact, the South Africans did very well and I was hopeful that we could swing the tide with them, if I could also get support from the local population. This was the difficulty because, although several chiefs supplied me with information on Frelimo’s movements, I could not rely on them when Frelimo threatened their people. Then, about two weeks ago, one of the South Africans came to see me in my apartment in my hotel, the Zambeze, when they were back for a break. He was their leader, an excellent man to have. O’Donnell was his name. He told me that they could not go on, unless they had some sort of air support and they did not have to dodge our Army, as well. I said that I could not guarantee non-interference from the Army, but I would arrange to have a plane on call and perhaps a helicopter for medi-vac purposes. Then da Silva came in, told him to get out, and said he needed to speak to me urgently, alone.” His mouth twisted with remembered humour.

“O’Donnell threatened to knock his block off, but I asked him to leave. Manuela came and the two of them told me I must not interfere with the South Africans, that they had plans for them that did not concern me. I was to keep my mouth shut and stay in the hotel or they would cut Rosa’s throat! Of course, I could not believe…Her own sister! To convince me, Manuela brought Rosa in and beat her up. Karate! Slammed her about until she lay bleeding on the floor while da Silva kept a gun on me!” Barros downed his beer in a couple of swallows and poured another. When he continued, his voice was calm, again.

“An hour later, O’Donnell fell from the balcony to his death. He must have been pushed, but one of his men saw it happen and insists it was an accident. I can’t believe that! The rest of the South Africans were locked away until they brought them here a couple of days ago. Another South African, Sanderson, his name was, was here with Manuela and da Silva -”

“Sanderson! Where is he now?” demanded Brand, his voice hard.

“An associate of Manuela’s, I was led to believe. I met him a couple of month’s ago. He was helping her to recruit mercenaries, she said. I didn’t like him, he was very arrogant. I didn’t try to find out more about him. I trusted Manuela… I should have looked into it, it might have given me a clue what Manuela and her communist friends were up to. I understand he had something to sell to the Communists, I don’t know what. Manuela trained him to jump from an aircraft, here. He and the others left this morning to jump somewhere. Manuela said the less I knew, the better, when I asked. But, when the Dakota came back, Manuela said that everything had gone wrong and that da Silva had fallen out of the Dakota, to his death. Sometimes I wish it had been Manuela that fell without a parachute! Mother of Christ, that I could have spawned such a devil! She is utterly without soul or conscience…” Barros was close to breakdown then, but in an uncomfortable minute or two, he pulled himself together. Cecile felt an overwhelming pity for the man and surreptitiously wiped the corner of her eye.

“The pilot,” Brand asked, gently. “Was he one of them?”

“I think so. It was Manuela who persuaded me to take Pereira on about a year ago. He was a good pilot and gave me no trouble. Reis, the man you met, was the camp manager. He is really a good man, but he has no balls – excuse me, Senhora”, he said to Cecile, who was still wearing her fake wedding ring. “No backbone. He accepted a bribe to help keep Rosa and me here as prisoners.”

“Were the South Africans wearing uniforms?” asked Brand, shrewdly.

“I didn’t see then, but Reis told me they were dressed as South African paratroopers, armed, but their ammunition was, how do you say, false?”

“Dummy,” supplied Brand. “Blanks. You have no idea where they were going to drop? Their target? I have information that the place is a mountain, marked on my map as Serra Muambe. Do you know it? Would it be suitable as a Frelimo camp?”

“In my youth, I hunted there,” Barros said, thoughtfully. “It is an extinct volcano, there is water there… It would make an excellent place to hide. I don’t know why I never thought of it before…”

Brand offered him a lit match for the cigarette that he was going to light and in turn lit his foul pipe. Barros did not seem to notice. He leaned forward, pleading.

“Now, you will question my daughter. I beg you not to harm her. Whatever she has done, she believes in. But she is my flesh and blood…”

“That is up to her, Mr. Barros. My primary concern is the man who calls himself Sanderson and the threat he constitutes to my country. If I can, I shall help the other South Africans, but they brought this on themselves when they joined you as mercenaries. Beyond that -”

“But our common enemy is Communism, Mr. Hanekom! Can you not get at the men behind my daughter? Get them to release their hold on her? I will undertake to see that she has nothing more to do with them!”

“If, as you say, she believes in what she has done, then it is a doctrine that has a hold on her, not men.” Brand spoke with sympathy, but not with hope. “Do you have a radio here?”

“In both planes, of course, and one in the room next door. Why do you ask?”

“It is conceivable that your daughter has been in touch with this Frelimo camp, if there is one there, and may know what happened after the drop and what happened to Sanderson and the others. It is time I talked to her.” Brand got to his feet as De Souza came back.

“I’ve been through the whole camp. No sign of anybody. Perhaps this Campos has taken to the bush?” De Souza said. Brand asked Barros what sort of man he was.

“Yes, he is the sort of man that would run when things, how do you say, get hot?” Barros permitted himself a wan smile. “Yes, he would take to the bush.”

“Okay, Mr. Barros, thanks for your help. I’m going to ask that Duvenage watch to see that you don’t do anything foolish while we talk to your daughter. Would you show him the radio? Perhaps one of your Army contacts could use the information about the possible Frelimo camp on Serra Muambe? Wait until we give the go-ahead before you talk to them. Please prepare us some food, if you would be so kind and we shall need to spend the night here, it is too late to try and find Sanderson today, but we must be away at first light, tomorrow.”

Barros nodded. “Just be as gentle as you can with the girl, that’s all I ask. If you are not, I shall find a way of making you pay for it.” Their eyes locked for a moment and Brand knew it was no idle threat. It would not help to antagonise the man without cause, or he would have to spend the rest of his life watching his back.

Brand told Cecile to be watchful and to let Reis and Rosa out of their room, but not to leave the building. On the veranda, the tableau had not changed. De Souza joined them. Duvenage went with Barros. Brand went to Manuela.

“Miss Barros, we need to ask you some questions. You will please come with us.”

Before he could duck, there was warm spittle running down his cheek. He held his temper and wiped it off. “Take her to the workshop, De Souza. She knows karate, I understand, so be cautious. I’ll take your rifle.” He took the R3 from De Souza, who moved in on the girl. He left his guard down just enough to tempt her and she flashed a stiff-fingered blow at his throat. She didn’t see him move but the blow missed and her arm was suddenly behind her back, pinioned, her shoulder muscles in agony. She sucked for breath with a hiss. Brand realised, when he saw De Souza move, that he was far from soft. He led Manuela away to the workshop, near where the Bell waited with Bates in attendance. Brand brought him up to date, warned him about Campos and told him to refuel the helicopter. Then he returned to the workshop.

There were two Toyota Landcruisers fitted with wooden benches on the back for game viewing, and a swamp tractor with enormous balloon tyres that reached above Brand’s head. There were two short-wheelbase Landrovers, bare to the chassis in front, without their engines that lay on a greasy piece of tarpaulin. Along the walls were racks of spares, nuts and bolts and rusty hardware. In one corner was a portable welding plant and a forge. Near the latter was a huge blacksmith’s vice set in a concrete block. De Souza was holding Manuela near the vice.

“We’d better gag her,” he said, conversationally, “We wouldn’t like to upset her father with her screams. Bring me some of that rag from the bench, would you? And some flex to tie her arms and legs. She is such a beautiful girl; it is going to be a pity to spoil her face. You know, I thought that if she doesn’t talk with a bit of pressure in the right places, then we could take off her nose in the vice. What do you think?”

“No difference to me, George,” Brand said indifferently, “It’s not my nose. What about some acid? Some in those old batteries, over there.” He fetched some flex from the racks and the oily rag. De Souza applied a little pressure as Manuela struggled. Her back arched in excruciating spasms and she offered no resistance as Brand tied her wrists together behind her back, then her ankles to the concrete block of the vice. Her dark eyes blazed her hatred and she clenched her jaw as Brand approached with the filthy rag. De Souza’s square fingers moved to her neck. Suddenly she screamed, but Brand choked it off with the rag. He held it in while De Souza tied it in place with some electrical tape. She struggled awhile as the men stood back to admire their handiwork., then tears oozed out of her eyes and she her shoulders began shake with sobs.

“Do you think she wants to say something to the Capitalistic Pigs, Mr. Hanekom?” De Souza lit a cigarette. Brand shook his head and reached for his pipe.

“How can she? She hasn’t been asked any questions, yet. Perhaps I’d better ask them now so that she can nod her head when she’s ready to answer them.”

“She’s going to have difficulty nodding with her nose in the vice.”

“Ja, true. But she’s a resourceful girl; I dare say she’ll make a plan. Here are the questions, Miss Barros. Why were the South African mercenaries of your father’s in the Dakota and why did they jump over Serra Muambe? Why did Sanderson jump with them? What do you intend doing with the information that Sanderson is selling you? Is there a Frelimo camp at Muambe? How many radios do they have at this camp and who operates them? Were you in contact with this camp this morning, either during your flight or after the drop? What went wrong with the drop? Where is Sanderson now? Where are the other South Africans? Who is your contact at Muambe? What is your chain of command, your superior, their superior? Of course, I shall probably think of more questions as we go along, but these will do to start with.”

“She is going to have difficulty breathing with her nose in the vice,” De Souza observed.

“True. The gag in her mouth. Ah, well, a little nod will allow her to breathe again.’ Brand looked speculatively at his prisoner. Manuela was struggling with every fibre in her body. Brand cranked open the jaws of the huge vice. “Do you think she understands my English, George? Perhaps you should translate it all into Portuguese. I’m sure she’s not nodding.”

“You’re right,” said De Souza, applying his thumbs to the sallow column of her neck. The pain shot into her head and she tried to pull away, but down, down went her nose towards the vice until her face was between the gaping steel jaws. Brand sank to his knees to look at the no-longer beautiful eyes that were bulging in terror as Brand began to wind the handle.

Manuela’s head jerked up and down so that she bruised her cheek on the rusted steel. She was nodding.

To be continued…

I had about 60 jumps at the time. I had been a founding member of the Rustenburg Parachuting Club, then joined the Pretoria Parachuting Club where the story starts.

I had about 60 jumps at the time. I had been a founding member of the Rustenburg Parachuting Club, then joined the Pretoria Parachuting Club where the story starts. What about Sierra Mueda, the extinct volcano where the group is forced to jump into the arms of the waiting Frelimo group, and the journalist? No, not by that name, anyway. But on the aerial photos we were given in 1971 to map part of Tete Province east of Tete Town, lies one such mountain. I have never found a name for it, and we never went there as we were working around Bandar and Lake Lifumba when we were warned by the local folk that if we did not move out, we would be shot by Frelimo.

What about Sierra Mueda, the extinct volcano where the group is forced to jump into the arms of the waiting Frelimo group, and the journalist? No, not by that name, anyway. But on the aerial photos we were given in 1971 to map part of Tete Province east of Tete Town, lies one such mountain. I have never found a name for it, and we never went there as we were working around Bandar and Lake Lifumba when we were warned by the local folk that if we did not move out, we would be shot by Frelimo. I zoomed in. Wonderfully exciting. It was a disappointment, however, but also intriguing, to see the shine of three new tin roofs on the northern lip. Obviously recent. By zoom, I followed the track to get there from a few-huts little village called Namisseche. A very rough and tortuous track indeed, to those three new buildings. What are they doing there? Hunting? Prospecting?

I zoomed in. Wonderfully exciting. It was a disappointment, however, but also intriguing, to see the shine of three new tin roofs on the northern lip. Obviously recent. By zoom, I followed the track to get there from a few-huts little village called Namisseche. A very rough and tortuous track indeed, to those three new buildings. What are they doing there? Hunting? Prospecting? THIRTY FIVE

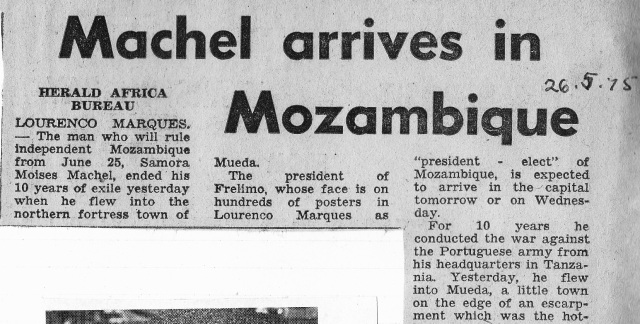

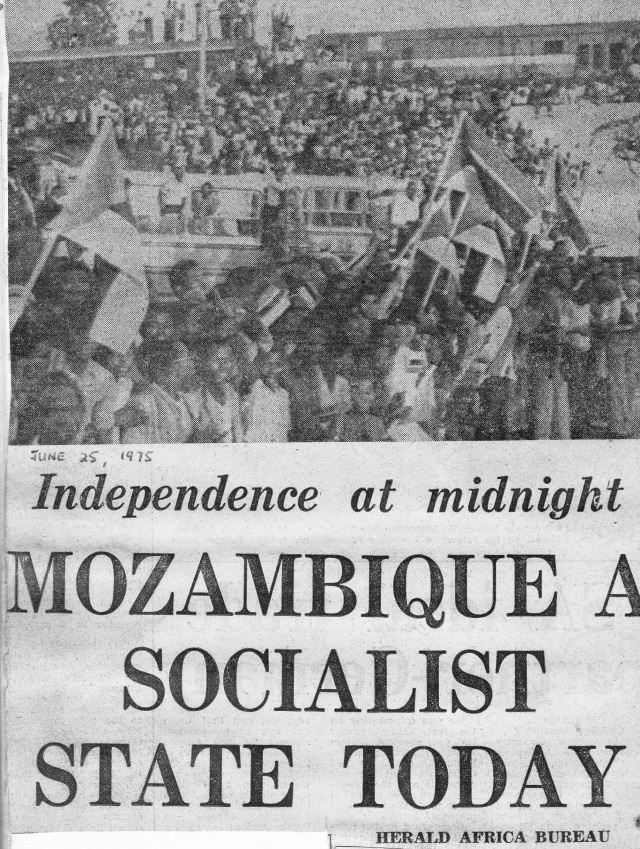

THIRTY FIVE On 7th September, 1974, representatives of the Portuguese Government and Frelimo met in Lusaka, Zambia, to sign the Acordo de Lusaka. The transitional period to independence had begun. Portuguese troops were sent home in ever increasing numbers, exiles returned, political prisoners were released. The dream of the People’s Republic of Mozambique became a reality on 25th June, 1975, the first fully committed black socialist state in Southern Africa. But, already, in May, a Russian delegation had been to discuss the development of the Lourenço Marques, soon to be Maputo, port facilities…

On 7th September, 1974, representatives of the Portuguese Government and Frelimo met in Lusaka, Zambia, to sign the Acordo de Lusaka. The transitional period to independence had begun. Portuguese troops were sent home in ever increasing numbers, exiles returned, political prisoners were released. The dream of the People’s Republic of Mozambique became a reality on 25th June, 1975, the first fully committed black socialist state in Southern Africa. But, already, in May, a Russian delegation had been to discuss the development of the Lourenço Marques, soon to be Maputo, port facilities…

Pires swung in at the Aerodrome, pulling up at the guard post. He pointed at the Barros Cessna 206 on the strip and told the soldier that they were expected. The guard stuck his cigarette back in his mouth and waved them in. Pires headed straight onto the hard-standing and stopped by the six-seater. Duvenage trotted over from where he had been chatting to some Air Force men. Brand introduced the agent to the two friends. It was just after one o’clock; siesta time. The tarmac threw up a vicious glare. It was the only piece of tarmac for hundreds of kilometres; all the roads were sand or metalled. The buildings were covered with dust; even the newly arrived Cessna already had a film on it.

Pires swung in at the Aerodrome, pulling up at the guard post. He pointed at the Barros Cessna 206 on the strip and told the soldier that they were expected. The guard stuck his cigarette back in his mouth and waved them in. Pires headed straight onto the hard-standing and stopped by the six-seater. Duvenage trotted over from where he had been chatting to some Air Force men. Brand introduced the agent to the two friends. It was just after one o’clock; siesta time. The tarmac threw up a vicious glare. It was the only piece of tarmac for hundreds of kilometres; all the roads were sand or metalled. The buildings were covered with dust; even the newly arrived Cessna already had a film on it. In the cockpit of the Dakota, Manuela had immediately recognised her father’s Cessna. She cursed, tugging Cecile’s pistol from the pocket of her leather flying jacket and yelling to van Rooyen who was still working on his precious radios. Five minutes would have seen them ready, synchronised, four different frequencies simultaneously ready to unlock, arm and fire the radio detonators of four tons of high explosive. In forty-one minutes the murderous signals would have been sent out. She screamed into the walkie-talkie in her hand to Theo in the truck to come back.

In the cockpit of the Dakota, Manuela had immediately recognised her father’s Cessna. She cursed, tugging Cecile’s pistol from the pocket of her leather flying jacket and yelling to van Rooyen who was still working on his precious radios. Five minutes would have seen them ready, synchronised, four different frequencies simultaneously ready to unlock, arm and fire the radio detonators of four tons of high explosive. In forty-one minutes the murderous signals would have been sent out. She screamed into the walkie-talkie in her hand to Theo in the truck to come back. TWENTY EIGHT

TWENTY EIGHT

TWENTY FIVE

TWENTY FIVE The midmorning sun threw a vicious glare off the planes, the roofs, and the shining tarmac itself, so that the majority of onlookers in the concourse of Manga Airport, Beira, including Morné Brand, wore sunglasses. A DETA Airways Boeing 707 from Lourenço Marques touched down with minimal bounce and little white puffs of smoke exploded from the wheels. In less than seven minutes of its coming to a standstill in front of the terminal, the first passenger was squinting into the glare from the top of the stairs.

The midmorning sun threw a vicious glare off the planes, the roofs, and the shining tarmac itself, so that the majority of onlookers in the concourse of Manga Airport, Beira, including Morné Brand, wore sunglasses. A DETA Airways Boeing 707 from Lourenço Marques touched down with minimal bounce and little white puffs of smoke exploded from the wheels. In less than seven minutes of its coming to a standstill in front of the terminal, the first passenger was squinting into the glare from the top of the stairs. TWENTY TWO

TWENTY TWO NINETEEN

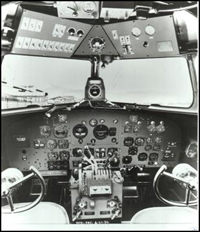

NINETEEN Rafe Schulman was wishing he could get at the controls of the Dak, he told Geoff. It was a few years since he had flown one, but he knew that he wouldn’t have any trouble. God, if he could only get in there. He knew that all of them were keyed up with this comparative freedom after the routine of their prison. Perhaps they’d get a chance before they were forced to make this jump. He was sure that they would not survive it, but he could not say why he thought so. Why did they want them to jump? He thought he was the only one to have jumped under full kit, in combat conditions; he was the only true Parabat. Half of the others had probably forgotten how to roll, having been spoilt for so long under their luxury sports parachutes – their Papillons, Para-Commanders, Clouds and the like. Geoff agreed.

Rafe Schulman was wishing he could get at the controls of the Dak, he told Geoff. It was a few years since he had flown one, but he knew that he wouldn’t have any trouble. God, if he could only get in there. He knew that all of them were keyed up with this comparative freedom after the routine of their prison. Perhaps they’d get a chance before they were forced to make this jump. He was sure that they would not survive it, but he could not say why he thought so. Why did they want them to jump? He thought he was the only one to have jumped under full kit, in combat conditions; he was the only true Parabat. Half of the others had probably forgotten how to roll, having been spoilt for so long under their luxury sports parachutes – their Papillons, Para-Commanders, Clouds and the like. Geoff agreed.